Banking on its sustainability credentials, the pearl could potentially become the world’s first ‘nature positive gem’ based on documented environmental benefits and social impact.

This article first appeared in Pearl Report 2025-2026.

The link between sustainability and pearls was first noted by Swiss gemmologist Laurent Cartier in 2010. Soon after, several sectors of the industry started pursuing their own sustainability agenda.

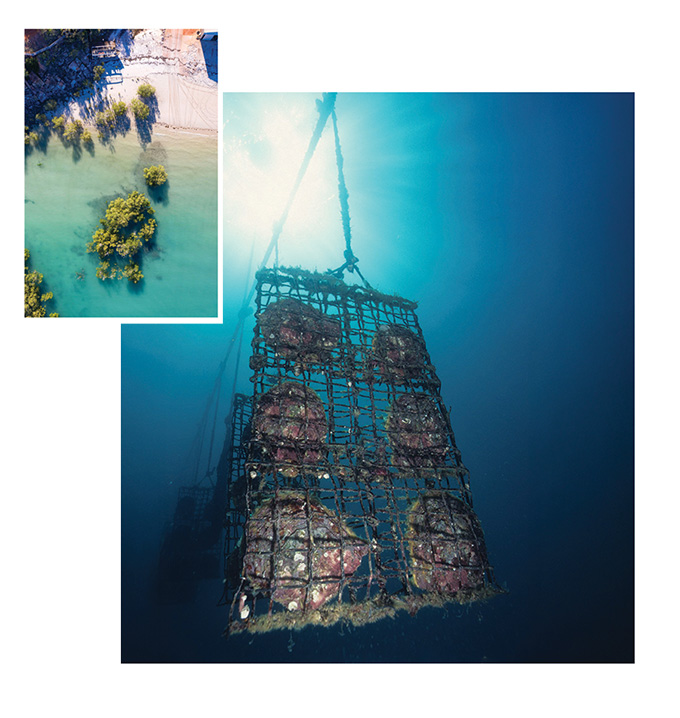

Australia achieved a Marine Stewardship Council-certified sustainable pearl fisheries status in 2017 while in 2018, J Hunter Pearls, Jewelmer and Paspaley Pearling Company launched “The Blue Pledge – Sustainable Pearls,” promoting responsible pearl farming to support conservation and social enterprise.

A new generation of consumers is reshaping the jewellery industry. Reputation and trust are replaced by transparency and traceability while voluntary Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) efforts shift to financial Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) standards. Code of Practice (CoP) and Chain of Custody (CoC) protocols have become standard, and technology now enables unique credentials for individual products beyond category certification.

Pearls are traditionally valued based on physical attributes that reflect the journey of the mollusc it grew within. Therefore, there is a natural incentive for pearling companies to look after their people and the molluscs, which will grow the pearls.

Most producing countries have exceeded their compliance requirements and created voluntary social and environmental codes of practices to guide responsible pearlers and farmers.

Industry players and stakeholders acknowledge that increased transparency around geographical origin and social and environmental impact can deliver substantial value, ranging from social licence to operate to enhanced natural capital – all of which may also amplify storytelling at retail level.

Natural capital consists of four categories of ecosystem services: Provisioning, regulating, supporting and cultural.

Nature positive gems

Could pearls be the first nature positive gems? Evidence supports this theory.

Results of Life Cycle Assessments (LCA) conducted in Japan and Australia in 2023 indicated a very low emission footprint for saltwater pearls, ranging from a few grams to a few kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2Eq) per harvested pearl.

For context, a typical car journey of just 3 kilometres produces approximately 1kg of CO2Eq emissions. A pearl farm producing 10,000 pearls per hectare (each with a 1kg carbon footprint) requires US$1,000 in carbon credits at US$100 per tonne, or just 10 cents per pearl.

Oysters also help improve water quality. Excess nutrients in oceans cause eutrophication, harmful algal blooms, oxygen depletion and shifts in species composition. Oysters naturally filter and remove these nutrients while feeding. Assuming one hectare of pearl farm produces 5t of oysters, which then remove 50kg of nitrogen valued at US$100/kg and 2.5kg of phosphorus valued at US$500/kg, the total bio-extraction equivalent value would be US$6,250.

Farming gears such as ropes, baskets and nets hosting the oysters, and the oysters themselves, likewise provide support, shelter and food – further boosting biodiversity. Studies estimate the value of catchable fish in an oyster-suitable marine environment ranges from US$1,000 to US$5,000 per hectare.

Meanwhile, pearl farming is labour-intensive, creating direct skilled employment in often remote areas, which can be complemented by education and empowerment opportunities for surrounding communities. Labour costs attached to one hectare of pearl farm alone can account for up to 30 per cent of pearl revenues generated at farm gate.

Marine pearl farming’s environmental impact varies significantly depending on cultivated species, farming methods and the environment. The above assumptions, however, support pearl farming’s nature net positive potential where the value of benefits exceeds the costs.

As such, there is a need for a more comprehensive evaluation through species- and location-specific measurement pilots to confirm these estimates. Community and ecological value alongside economic metrics should be recorded using a balance sheet.

How can value be realised?

Demonstrating value to ecosystems and communities provides a variety of benefits: For producers, it enhances social and environmental licences to operate and improves productivity while for traders and retailers, it ensures compliance and creates compelling sustainability and storytelling opportunities.

Collecting and processing consistent data presents significant challenges, given the complexity and length of the pearl value chain.

Track-and-trace initiatives are designed to associate products with verified sustainability credentials. Meanwhile, ongoing dialogue is centred on establishing a global framework and reporting system that accommodates the transparency requirements of retailers as well as the needs of small, non-vertically integrated farmers.

In 2024, Onegemme, a B2B trading platform for single-origin pearls, partnered with Provenance Proof – a blockchain traceability service from Gübelin – to provide transparent origin tracking and social and environmental impact profile.

Each pearl sold includes a transferable provenance certificate, impact profile and detailed description.

The World Jewellery Confederation (CIBJO), for its part, is adding a 10-page section on sustainability initiatives by pearl-producing countries to its Pearl Guide. This supplement builds on previous content about responsible pearling and its community and environmental benefits introduced in Shanghai in 2024.

The Gemological Institute of America (GIA), meanwhile, reinforced its pearl evaluation capabilities by introducing a nacre continuity scale, which refers to the thickness and evenness of layers that form on a pearl. It was unveiled in May 2025.

These changes highlight how a mollusc’s journey shapes a pearl’s physical traits. Social and environmental factors affect not only the pearl’s appearance but also its value.