As consumer scrutiny of jewellery’s impact on people and the planet intensifies, JNA explores how miners, dealers and jewellers alike are working towards sustainable supply chains and greater transparency and accountability in the sector.

This article first appeared in the JNA April/March 2023 issue.

What does responsible sourcing of gemstones entail? Does it start and stop at the integrity of the gem material? Is there room for the realities of underdeveloped economies? Some believe the industry uses culture and poverty as an excuse to justify the lack of responsible behaviour. But if everything is brushed under the culture carpet, how will matters ever improve? Others bristle at the mere mention of a mining company. Learning from the past is vital for future growth and improvement. But is using a historical reference in a modern context responsible?

The foundation of responsible sourcing must be the integrity of the gemstone. This entails using accurate language to describe the stone, and full disclosure of enhancements or treatments done to improve its appearance.

Supporting the industry in this first layer of the responsibility cake are organisations such as CIBJO (The World Jewellery Confederation), which has published guidelines known as Blue Books for Coloured Gemstones and for Responsible Sourcing. The gemstone book details nomenclature for description of stones and disclosure of treatments and provides vital information to aid responsible behaviour. In the Responsible Sourcing Blue Book, CIBJO clarifies that The Responsible Sourcing Policy is guidance for responsible business practices and supply chain due diligence: It is not a system to address traceability of precious metals or gem materials to a mine source and cannot be described or interpreted as a chain of custody.

The US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has published Green Guides, which provide detailed information related to responsible behaviour. The Jewelers Vigilance Committee (JVC) has created an all-in-one resource book: “Understanding the FTC Guidelines.” Unlike CIBJO, FTC is empowered by law to punish offenders.

The next layer in the responsibility cake is certification and endorsement. Here, membership in trade bodies such as the American Gem Trade Association (AGTA), CIBJO, the International Colored Gemstone Association (ICA) and the Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC) can help.

For a standalone entrepreneur, comprehensive guideline documents, audits and membership-based organisations can be daunting. To address this, the Coloured Gemstone Working Group (CGWG) created The Gems & Jewellery Platform in 2021. This is a digital space where anyone can access free resources and capacity-building tools to learn about responsible behaviour and implement best practices within their business. CGWG was created in 2015 by Tiffany & Co, Swarovski, Richemont, LVMH, Kering and Gemfields. The Muzo Companies joined in 2017, Chopard in 2019 and Audemars Piguet in 2022.

Pioneers

While many initiatives are recent and still developing, certain individuals and organisations have been at the forefront of responsible supply chains for decades.

Columbia Gem House wrote its company protocols regarding responsible sourcing 21 years ago after working on a project in Madagascar for the World Bank related to poverty alleviation via gemstones. When company founder Eric Braunwart ruined one of his Ferragamo shoes stepping into an open sewer in Antananarivo, he realised his one shoe cost more than the average annual income in Madagascar at the time.

“That is when we started looking at how our decisions could bring more benefits to the cutters and the miners. Supportive supply chain best describes what we do, whether working directly with a miner or an agent, to better understand the conditions under which a gem was extracted. Tracing gemstones means nothing unless you are willing to act on issues if you see them come up,” Braunwart remarked.

Emerald miner Belmont was also ahead of its time, spearheading sophisticated mining initiatives for over four decades. On top of other measures to reduce emissions, it will start operating its own 1.5MW photovoltaic power plant this year, allowing its mine to run on renewable solar energy. The company aims to achieve net-zero emissions in the near future.

Belmont President Marcelo Ribeiro said, “Although our industry has been talking about sustainability and traceability for many years, it is very conservative and different markets are in different levels of maturity regarding this subject. This is a theme that is just gaining relevance.”

Gemfields, meanwhile, is the only gem mining company to regularly publish detailed auction results, bringing much-needed transparency to the rough gemstone sector. To magnify their charitable work in Africa, it established the Gemfields Foundation in January 2021 and, that July, introduced ‘G-Factor for natural resources,’ a measure for calculating the percentage of a nation’s natural resource wealth that is shared with the host government, which they voluntarily publish.

According to CEO Sean Gilbertson, Gemfields believes that gemstone resources belong to and are the birthright of the host nation’s citizens. The miner sees itself as the temporary custodian with a duty to deliver the maximum benefit from those resources – monetarily, socially, developmentally and environmentally.

“If one avoids shortcuts, be it in the approach to health and safety, environmental best practice or full compliance with mining laws, then it is always going to be more expensive. Our approach has inevitably ruffled the feathers of parties who have benefitted historically from the ‘grey areas’ afforded by what has in the past been a complex and ‘opaque’ industry. There remains a strong financial incentive to buy cheap gems from spurious sources, and often the mine of origin is not known,” shared Gilbertson, adding that Gemfields is keen to instil in the industry a “mine-of-origin” model rather than the prevailing “country-of-origin.”

Tech solutions

Technology and digital marketplaces also facilitate responsible sourcing. The Emerald Paternity Test by Provenance Proof provides a foolproof mine-to-market chain of custody. Launched in 2017 with Gemfields and Belmont, the process involves immersing rough emeralds at the mine of origin in a solution containing nanoparticles, which get embedded in the natural fissures of a rough emerald, surviving the cutting and polishing process that transforms the rough into a facetted gem. This is supported by a digital ledger or Provenance Proof blockchain. Once set and sold in a jewel, customers can bring the jewel for testing to check the mine of origin.

But whether technology translates into responsible sourcing depends on the behaviour of the stakeholders involved and the integrity of the information provided.

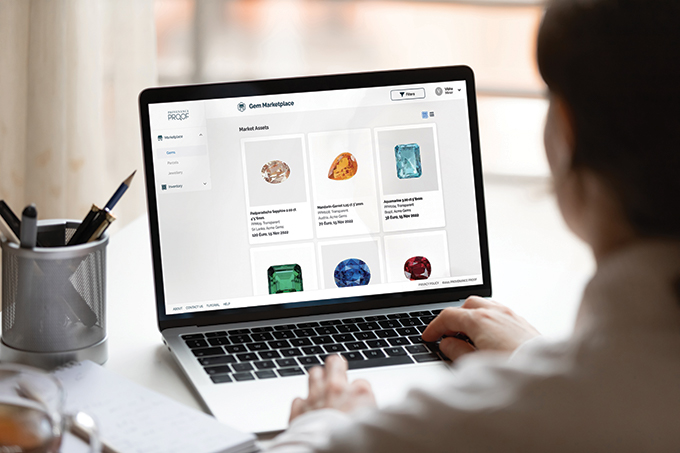

Provenance Proof Director Klemens Link said, “Our latest venture is the Provenance Proof Marketplace, which gives the gem industry access to buy transparently traded gems. We believe provable transparency and traceability empowers trust. It is also important for us that the artisanal mining sector is not excluded.”

To that end, many initiatives by Provenance Proof remain free-of-charge. This year, it will be adding more third-party verified information on stakeholders and on asset level, for instance, through gemmological laboratories, auditing organisations, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) or government authorities.

Mining operations

Fura Gems, which operates large-scale emerald, ruby and sapphire mines in Colombia, Mozambique and Australia, has fast-tracked growth by taking over prevailing mining operations and deposits. Its Australian mine is already an RJC member, and Fura has registered with RJC with the aim of completing certification for the group and all its other operating sites by the end of 2023.

Montana in the US has emerged as a key source for responsibly mined sapphires, courtesy of Potentate Mining, which owns around 90 per cent of the most prolific deposit in the Rock Creek region.

Due to strict environmental regulation and higher costs of a first-world economy, Potentate runs a lean operation and has undertaken several conservation initiatives such as using recycled water to process production and, despite the 3,300 acres at their disposal, not disturbing more than five acres at a time without rehabilitation of the land. Potentate's offering of traceable, responsibly mined sapphires is an attractive feature for many buyers. Most Montana sapphires require heat treatment but, for some, the lower risk in comparison to buying from Africa where it is more challenging to trace the stones to the mine and extraction circumstances, outweigh the unusual pale-green and blue-green colours of the Montana production.

Another venture in the West offering responsibly mined, traceable rubies and pink sapphires is Greenland Ruby. Like rubies from Mong Hsu in Burma, almost all of Greenland's production is heated with borax. Some would immediately label them as glass-filled but there is a technical difference between “heated with borax” and “glass-filled” rubies, as the company explains on its website.

“I recently saw top-quality 6mm red ruby beads from Longido, Tanzania,” explained gem merchant Jeffrey Bergman SGC SSEF. “They were unheated and cost US$20 per bead, which would have been US$200 if they were from Greenland.” The morale of the story is that stones traceable to a responsible source, combined with a good dollop of sales and marketing will fetch a premium, irrespective of their unconventional colour and treatment.

Looking east, Fuli Gemstones offers responsibly mined peridot from the foothills of China’s Changbai mountains. Established in 2015, the vertically integrated company currently supplies peridots from its bulk-sampling operations. Once full-scale mining starts, it aims to become a dominant player for peridot. Fuli has already begun to reshape the demand landscape for peridot, aggressively marketing itself as a responsible mine.

Community impact

Other mine-to-market initiatives include Moyo Gems, which offers retailers and jewellery manufacturers the opportunity to source directly from small-scale mining communities in East Africa. Virtu Gems is an online source connecting miners and cutters in Africa to the industry and consumer-at-large.

Cristina Villegas, director, Sustainable Markets for the NGO PACT said, "It is important to clarify that gemstone suppliers do not have to create a fancy responsible sourcing programme. They should understand their sources, choose one thing to work on with a mining community then document, commit, grow, and communicate to customers."

Gem Legacy, founded by US-based merchant Roger Dery, works at a grassroots level to provide basic tools to informal and small-scale mining communities and supports schools and skills development in East Africa.

Nigeria-focused Mina Stones and Zambia-based Jewel of Africa actively support the gemstone community in their respective countries.

“Most artisanal miners have traditionally been villagers discovering gem outcrops while on hunts after the harvesting season is over and before the planting season begins,” revealed Jewel of Africa Co-Founder Rashmi Sharma. “We are committed to ensuring that the communities we work with benefit from our purchases and that our activities comply with laws and regulations.”

Jewel of Africa is involved in a variety of charitable programmes, including a skills development initiative in cutting and polishing gems for underprivileged refugees with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Mina Stones Founder Lotanna Amina Okpukpara added, “By providing technical, financial and social inclusion support, we are helping miners and their communities receive equitable value for their resources and this is at the core of our sourcing process.”

Harsh realities

For the vast majority in the industry though, the incentive to buy cheap gems will always be strong, perpetuating a system of getting the lowest price at all costs and doing little or nothing to improve conditions throughout their supply chain. This traps people in poverty when communities are selling out of desperation.

Responsible sourcing is not a silver bullet. Marcena Hunter, senior analyst with Geneva-based NGO Global Initiative, said, “On the mining side, one has to look beyond the legality of the operation to whether it translates into local development gains. On the flip side, the few artisanal mining-focused initiatives that exist in the industry are benefitting a limited group of people. It is a very small portion of the market and will not move the needle in the larger scheme of things.” Insistence on traceability can sometimes push miners out of the supply chain due to lack of education and access to technological tools, empowering criminal actors, she added.

Another challenge the industry faces is dealing with countries where, for many, undervaluation of goods at the time of export or smuggling of rough gemstones has become the norm. Responsible merchants looking to import gems at fair values and via legitimate channels find themselves at a disadvantage. Independent geologist and mining consultant Zoe Harimalala Tsiverisoa, who is based in Madagascar, said, “Clients do not do due diligence regarding the items they buy, so sellers do not care about doing things properly. Responsible sourcing is possible and being carried out by select partnerships in the region.”

Seasoned gem merchant Guy Clutterbuck who has spent considerable time living and working alongside miners and merchants in Afghanistan, Brazil, Asia and Africa, encourages the gemstone sector to learn from the wine industry, which incorporates the story of the vineyard and the terroir of the host region in its narratives. For wines, this detailed level of storytelling is not considered marketing but an essential element to continuously attaining a higher value, he noted.

“With an ever-shrinking world, customers will increasingly want to know not only the geographic origin of their gemstone but the entire story related to its journey from mine to market. Responsible sourcing is no longer a choice but a necessity,” Clutterbuck said.

At some level, it seems as if responsible players in the industry are working within their silos. The large-scale mining companies and their auction partners are in one bucket, and members of the RJC and other associations have their own ecosystems. Dotting the rest of the landscape are niche mine-to-market projects created by gem merchants, manufacturers and retailers that support a responsible story for their customers. Sixteen years ago, barring one or two exceptions, none of these existed.

Border restrictions during the pandemic and higher travel costs have increased the industry’s dependence on reliable channels for responsible sourcing. Those pondering their next move can reflect on Villegas’ words, “There are many paths to positive social impact. Find out what countries your supply is coming from, then the specific region, and try to start there. Responsibility begins with your own supply chain.”