Traditional sources of financing for the international jewellery industry, particularly the diamond sector, have been drying up in recent years.

JNA looks at the financing options now available for the trade and

the creative ways some stakeholders are funding growth.

Financing in the gem and jewellery industry occurs along the entire supply chain, literally from mine to market. Money moves through the chain to the retailer, who may finance inventory, and ultimately to their customers, who may finance an engagement ring or other piece of jewellery.

Traditionally, industry players have relied on bank loans and unsecured lines of credit. Over the last decade however, the gem and jewellery landscape has been shaken to its core. The major tremors reverberating through the industry – the volatile global economic climate, bankruptcies, stricter regulations regarding money laundering, and reputational concerns, among others – have caused traditional lenders to become more cautious.

During this time, there have also been major shifts in the financial services industry itself, most notably due to digital transformations. This has led to the birth of strictly online neobanks and other alternative financing with their disruptive banking technologies. Both types are successfully competing with traditional banks around the world.

Banking on it

Banks began shifting out of the diamond sector over the last decade or so. “It started with Antwerp Diamond Bank (ADB), which had to close in 2014 due to issues faced by its parent, KBC Bank, stemming from the 2008 financial crisis, that had nothing to do with the diamond industry,” explained industry analyst Pranay Narvekar, a partner at Pharos Beam Consulting LLP. “Two years later, London-based Standard Chartered, which had aggressively entered the diamond financing markets, suffered losses and moved out of the diamond industry. ABN Amro also decided the diamond business was not a core business for them and, while they are not out of the industry yet, the bank has clearly pruned its businesses outside of Europe.”

After the highly publicised alleged US$2 billion loan fraud in 2018 perpetrated by jewellers Nirav Modi and his uncle Mehul Choksi against India’s Punjab National Bank, plus a number of unrelated loan defaults by other companies, Indian banks adopted a more conservative approach in lending to the industry. Aside from defaults, the diamond sector was also considered high-risk because of reputational and money laundering issues, requiring increased costs for banks.

Yet, “Financing the diamond trade remains a profitable venture for banks that are able to manage their risks properly. This is why the sector was – and remains – a niche sector, where a few banks, with the necessary risk management mechanisms in place, continue to lend to the trade,” Narvekar continued. Bank lines today are even underutilised, he added.

“We are in an interesting position today,” noted industry analyst Edahn Golan. “The cost of financing encouraged diamond firms, primarily in the midstream, to deleverage, to decrease their dependency on financing. And, with a decrease in demand for financing, some banks are pulling out, while others are interested in expanding their diamond portfolio.”

Although diamond financing continued to shrink in 2020, Golan noted that it was at a moderate pace. “After the decreased leveraging, especially in 2019, banks felt somewhat more confident about their clients’ good standing upon entering 2020,” he remarked, adding that these banks “understand the industry well and have found that, even during the Covid crisis, they can depend on the diamond industry to meet its obligations on time. These banks therefore actively sought out diamond firms to offer additional financing.”

In India, manufacturers find that banks are now relaxing their earlier stringent financial demands, said K. Srinivasan, managing director of Coimbatore-based Emerald Jewel India Ltd, one of the country’s largest gold, diamond, and coloured gemstone jewellery manufacturers. He shared, “Today, a company that is prompt with loan payments can benefit from a 20 per cent increase in outstanding credit limits.” According to Srinivasan, banks are still the primary institutions to loan money to the Indian industry. He also feels that the outlook for bank financing is bright. “We don’t foresee any problems in the near future,” he added.

Aside from ABN Amro, which maintains a presence in Antwerp after closing offices in Tokyo, Botswana, New York, Dubai and Hong Kong, LuxuryFintech Founder Erik Jens notes that other banks are still engaged in the sector, with India’s IndusInd Bank seemingly the largest since it acquired ABN Amro’s portfolio in 2015. The National Bank of Fujairah (the United Arab Emirates), with an office in Antwerp, is growing its portfolio as is the Israel Discount Bank with operations in New York and Tel Aviv. Banks with smaller exposure include HSBC (New York and Hong Kong), Emirates NDB, Mashreq Bank (Dubai), First National Bank (Botswana), Bank of Baroda (India), and Bank Mizrahi-Tefahot (Israel). The Eximbank of Russia entered the diamond lending sector last year and is likely to grow its exposure.

Narvekar adds that Indian public sector banks such as Bank of India and State Bank of India continue to lend to the industry as do some private sector banks that hold smaller portfolios with reduced exposure. KBC Bank and Standard Chartered in Belgium may still have some remnant borrowers from their earlier exposure in the business.

On a smaller scale, and at the opposite end of the mined diamond sector, is an example of bank financing for a company specialising in lab-grown diamonds. A die-hard entrepreneur, Gary LaCourt founded Wisconsin-based Forever Companies in 2004. “We worked hard to generate internal cash-flow and ‘bootstrap’ the company,” explained LaCourt. “As our growth rate ramped up, we needed expansion funds. With an early track record of profitability and positive cash flow, we were very ‘bankable,’ so we went to the bank.”

His financial success was not just based on funding, but on deep-rooted, interconnected money relationships. “There is financing available for companies with a great idea, a compelling and logical business plan, and great leadership,” he advised. “In nearly 40 years, I’ve never seen a better and more exciting environment.”

“In China, generally only government-owned jewellery companies can get bank loans,” said Chen Shen, owner of Shanghai-based Skywalk Global, a gemstone and jewellery consulting company. "Others often leverage their real estate holdings or turn to private investors.”

Shen cites the example of Lao Feng Xiang (LFX), one of China’s largest jewellery companies. “When it expanded into Hong Kong, Canada and the US, it secured a US$200 million low-interest loan from Hong Kong’s financial markets. Along with payment terms from diamond companies, it didn’t spend one penny from its mainland China operations,” he said.

Alternative mindset

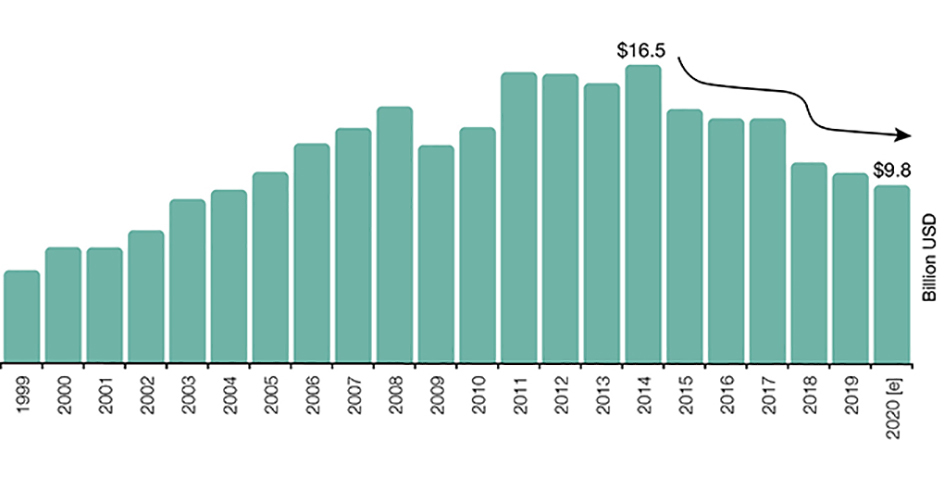

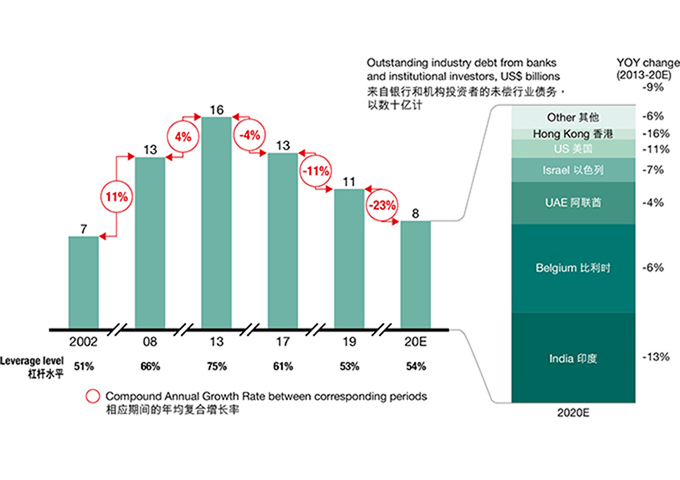

Despite a number of welcome success stories, financing in the diamond industry has been shrinking over the last decade. Although it reached a peak of US$16.5 billion in 2014, it had declined to about US$9.8 billion by 2020, according to Edahn Golan Diamond Research Analysis.

Bain & Company’s Brilliant Under Pressure: The Global Diamond Industry 2020-21 report, commissioned by the Antwerp World Diamond Centre, also noted that diamond financing continued to decrease, aligning with reduced activity levels in 2020.

According to the report, while the midstream segment lowered its debt by half compared to its peak in 2013, financing decreased due to lower trading levels and a higher reliance on self-financing.

“Larger midstream companies with transparent operations continued to access financing from big banks, while alternative financing options (peer-to-peer financing) emerged for smaller players. Large midstream companies, banks in the Middle East, and specialised funds were made available to provide additional financing in the sector,” the report continued.

Indeed, as banks began pulling back, others saw opportunities to forge ahead with alternate forms of lending. One of these forward-looking entrepreneurs is Chris Del Gatto, founder of luxury estate jewellery business Circa.

Understanding the challenges facing the diamond and jewellery industry, Del Gatto created New York-based Delgatto Diamond Finance Fund (DDFF) in 2018 and has since financed more than 200 companies around the world.

“We offer an easy and inexpensive way to access capital that is not restrictive, plus a no-cost marketing option allowing for greater profit than wholesalers currently possess. For the most part, we market our clients’ goods to a global network of buyers,” he explained. “DDFF has taken much of the risk out of financing the industry because we do not lend on paper as banks do.” Instead, they work with physical collateral in the form of rough and polished diamonds (60 to 65 per cent of business), while high-value gems, high-end watches, and jewellery (manufacturers, retailers, upmarket antique jewels) make up the rest.

“We work with good solid companies, ranging from US$10 million in turnover to those with US$600 million to US$800 million and even up to US$1 billion, with loans that start at around US$100,000,” Del Gatto revealed.

Extending its holistic approach, DDFF acts as an office for financing overseas buyers, mainly from Antwerp, India, Dubai, and Israel, who want to present goods to clients in the US. “This is extremely successful for companies that do not want to spend large amounts to have a US office,” he said, adding that DDFF holds the merchandise.

Noting that commercial banks will likely always play some role in the sector, Del Gatto feels that the “real future, given the nature of our industry, is going to be with alternative lenders for what we hope will become a new paradigm within this historically rich and vital industry for many years to come.”

When it comes to coloured gemstones, Austria-based Bryan’s Fine Gems is one of the very few, if not the only company, specialising in loans collateralised by top-quality gemstones. “We provide a service to people from our industry who need short-term funding to purchase a parcel of rough, for example, or for other reasons,” said owner Bryan Pavlik. “Dealing with important gems is not for everyone; it requires thorough knowledge of the stone and the market. There is no reference price list as exists for colourless diamonds.”

The loans are secured by insured gemstone collateral and start at US$30,000 up to US$300,000. “The time frame ranges from two weeks to six months, but we are flexible, and the owners may prolong their loans at any time,” Pavlik added. He also reveals that defaults are low – around 6 per cent. “The transactions are all done in person because it’s nearly impossible to judge a high-value coloured stone online.” He laments that he has more demand than he can handle, noting that “the market for this service is huge.”

Enter Fintech

Short for financial technology, fintech was first used to describe technology used in the back-end systems of financial institutions. Today, it describes new tech that improves the delivery of financial services, providing innovative ways for people to transact business. There are four general categories of fintech users: Banks; their business clients; small business B2C; and consumers.

The first fintech company focusing on the global diamond industry connecting vendors and buyers through an online trading ecosystem is Ramat Gan-based UNI.Diamonds. Launched in 2018, it moves the traditional trading experience into the new digital arena, where it facilitates buying and selling while taking care of logistics and security for delivery around the world. In addition, UNI.Diamonds can provide financing.

“Our financing process is quite simple,” explained CEO Mahiar Borhanjoo. “When diamonds are provided to us, we use the live data on our platform to evaluate the stones based on 24 unique parameters. Combining live market prices and these parameters allows us to be precise in our pricing, and we provide 50 per cent financing for the polished diamonds that we fund. Our funding is backed by the inventory of natural diamonds.”

According to Borhanjoo, UNI uses blockchain to allow full future traceability of diamonds that it finances because traceability and transparency are important to the company and its customers. “UNI's aim is to bring transparency and trust in every product that we finance and sell,” he remarked.

In the world of fintech, some companies do not directly provide finance but facilitate financing options. Jens' LuxuryFintech is involved in luxury gems, jewellery, and fine art. Jens, the former global head of ABN Amro’s diamond and jewellery client services, said, “Fintech-related lending is different from traditional lending in that it is technology-based in order to improve and automate the delivery and use of financial services. Fintech is utilised to help companies and consumers better manage their operations and lives by using specialised software like blockchain and algorithms with artificial intelligence.”

“For the gemstone and art sector,” Jens continued, “this technology creates true provenance, visibility, and authenticity in the flow of money and goods, providing new opportunities that allow for quick digital insights, insurance, delivery, and invoicing. For rough gems, blockchain tracking offers transparent financing while reducing credit and reputational risks since it brings asset-backed secured lending rather than just inventory or trade receivables as collateral.”

Based in Amsterdam and New York, LuxuryFintech is involved with both established and start-up companies that promote asset-based financing and secure lending, online payments, art registration, insurance, and trading platforms through fintech, including blockchain.

Support of the crowd

Millions in financing at the upper end of the gem and jewellery spectrum is one thing, but what about the opposite extreme? What about small companies with much smaller financial needs? One of the most novel approaches to raising money that has come with the digital age is crowdfunding. By using social media to create awareness, an individual, company or organisation can reach more potential donors – family, friends, strangers, other businesses – than traditional types of fundraising.

There are many platforms available, all with different features, fees, and support. One of the most popular is New York-based Kickstarter, founded in 2009.

Jewellery designer Wendy Brandes was an early adopter of Kickstarter. In 2010, she raised US$10,115, in her goal of US$7,000 for the creation of her “OMG” rings, which were given to those who pledged US$300.

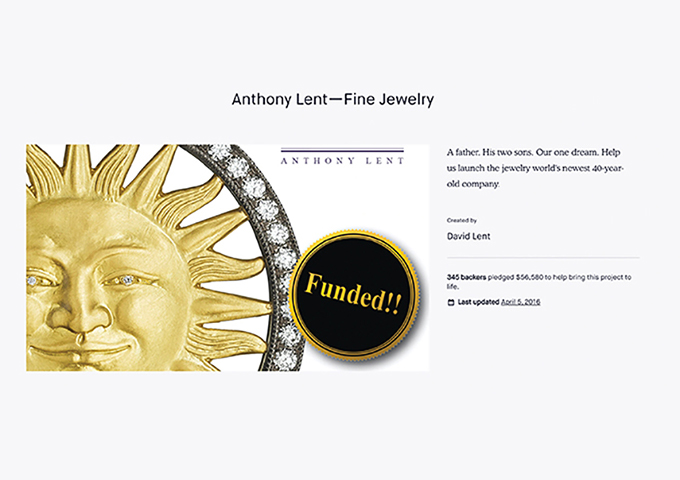

In 2016, New York-based jewellery manufacturer Anthony Lent turned to Kickstarter in the hope of attracting money for a specific project. Telling their story in words, photos, and video, they received pledges from US$1 to US$10,000, and raised US$56,580, exceeding their “ask” by US$6,580.

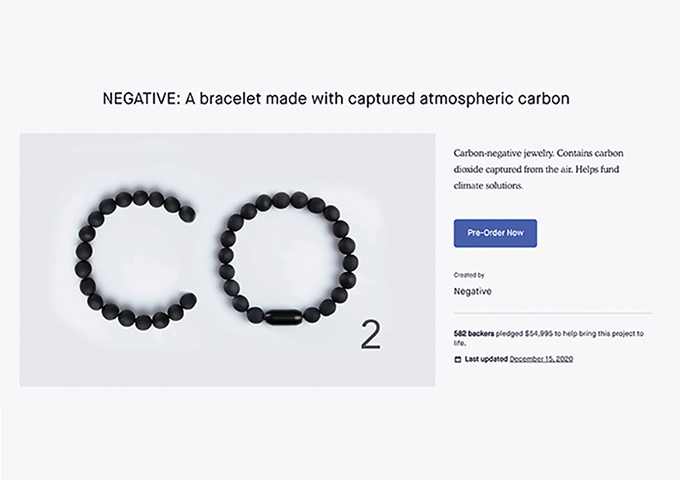

Combining jewellery with eco-friendly products – made from an innovative technique that captures carbon dioxide from the air – proved a winning strategy for California-based jewellery start-up, Negative. In December 2020, it raised US$54,995 from 582 backers on Kickstarter for producing its carbon-negative bead bracelets.

When fintech entrepreneurs Sukhi Jutla and Ram Krishnna Rao wanted to raise funds for MarketOrders, a London-based B2B platform for independent jewellery retailers and suppliers, they turned to the crowdfunding site, Crowdcube.com. With over US$500,000 raised from 214 investors, they are digitising and facilitating the entire customer journey, from ordering online to payments and shipments.

Indirect financing

There is also a significant amount of funding that benefits the gem and jewellery industry as a whole, and that is indirect financing. These monies come primarily from a number of international institutions, including the European Union and World Bank, as well as various governments and private foundations.

“These funds are generally given to governments and their appropriate ministries, which then redirect them to NGOs, co-ops, consulting firms, and non-profits to plan and/or execute policies and projects,” said Jean Claude Michelou, founder of Thailand-based Imperial Colors and advisor to international organisations. “The money may be used for developing national policies, infrastructure, training artisanal miners and cutters, improving living conditions in mining communities, and more.”

For Amina Okpukpara, owner of Nigeria-based Mina Stones and an advocate for the gem and jewellery industry in Africa, the support of international organisations is important for the sector to expand and succeed.

“While there is a small amount of bank financing available, the guarantees and collateral demanded of small companies make it nearly impossible to get the funds directly,” she said.

Mining consultant Amanda Lumun Feese agrees. “The Bank of Industry, which partners with the Central Bank of Nigeria, will afford micro-loans to segments of the industry if they meet specific requirements, but these requirements, in most cases, are too steep for artisanal miners and small businesses to meet,” she said.

During the Covid lockdown, Okpukpara and a few friends raised money to micro-finance artisanal miners in Nigeria so they could keep food on the table.

There can be no doubt that 2020 was not a good year for the gem and jewellery industry, with sales plummeting, especially in the spring. By year end, however, the initial panic caused by the pandemic had eased and signs of recovery appear to be happening around the world. Stimulus payments by major governments have helped the industry and consumers alike, while low-rate loans are aiding businesses to weather the storm.

Although the shift towards online had been growing, in both sales and financing, Covid accelerated the process. While the industry is still not out of the woods, and the future remains uncertain, the sector has proven itself to be resilient and adaptable… definitely reassuring.