Through meticulous design and precise execution, lapidary masters unveil the inner beauty of the stone, turning it into a vessel of philosophical thought and spiritual narrative. Acclaimed gem cutter Victor Tuzlukov and gem carver Naomi Sarna reveal the thought and creative process behind their works.

Gemstones are wonders and legacies of nature. But while the time spent fashioning a single stone is dwarfed by the millions of years nature spent forming the gem, the cutter's and carver's skill level has a profound – and often irreversible – impact on its beauty, value and significance. In the right hands, the gem comes to life.

Award-winning lapidarists Victor Tuzlukov and Naomi Sarna respond to the call of the gem. Pilgrims to perfection, they seek to reveal the full beauty of gemstones through the art of gem cutting and carving. This is likewise their advocacy – both actively organise gem cutting and carving guilds for like minds to share their passion, skills and insights on the craft. Their world-class skills are evident in their masterpieces that are on permanent display at the Smithsonian Institution.

Creative process

Famed lapidarist Victor Tuzlukov uses gemstones as vehicles for self-expression. Founder of the Russian Faceters Guild, he takes a philosopher’s approach to gem cutting – imbuing the stones he facets with spirit, body and soul.

“The Michelangelo and Leonardo era of gem cutting lies ahead. Nowadays, very few intentionally use the gemstone as an instrument to express ideas, thoughts, emotions or concepts. Modest steps to this goal are now being taken. The first drops are not the storm, but they foreshadow it. Perhaps centuries later, people would consider these days as the official starting point – when a new kind of art was born,” the

lapidarist remarked.

Tuzlukov embarked on his Lapis Philosophorum or Philosophical Stone project in 2009. The first collection comprises 10 gemstones with parables and images. Within each stone, the gem artist created images through specially faceted designs that reflect the parable.

Though created independently, when all 10 stones were exhibited for the first time in 2014 in France, they were found to symbolise stages of the evolution of the universe and of mankind. The entire collection represented the whole cycle of evolution. The whole idea behind the Philosophical Stone collection was to show that a gem could be a vector of ideas and concepts, much like other art forms such as music, painting or literature. The collections that followed – Elements, Flowers and World Heritage – have strengthened and deepened this concept.

Cultural microcosm

The World Heritage is Tuzlukov’s lifelong and larger-than-life project that started out as an attempt to capture the essence of various cultures.

Its first gemstones were faceted with ornaments, images and symbols representative of the cultures of China, Japan and

India respectively.

World Heritage Gemstone No. 1 is From The Emptiness (China), a 187-carat fire citrine with 712 facets. At the centre of the gem’s crown is the Chinese Yin Yang symbol of duality, carved with 60 facets that allude to the 60-year cycle of the Chinese calendar. Surrounding the symbol are quadrangles and hexagons that form the awakening dragon that is often used to symbolise China.

As the World Heritage project progressed, Tuzlukov realised that the deeper the truths expressed by different cultures, the closer they were to each other in essence; they vary only in the means of expression, just like numerous branches stemming from the same hidden roots. This prompted him to expand the project’s parameters, moving from the concept to actual images; from the symbols to their representations.

The shift was prompted largely by the 2019 fire that ravaged the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris.

“This tragedy made me realise the fragility of our cultural heritage. What was created and kept for centuries could be destroyed in a matter of` hours. I wanted to immortalise the memory of the great cathedral as an important part of our world cultural heritage. Interestingly, the first gemstones of the project organically fit into this theme, as though they were created in these frames,” Tuzlukov explained.

The Notre Dame experience cemented Tuzlukov’s concept for World Heritage: Focusing on how different cultures expressed the tenets of wisdom, love, beauty and harmony through their own icons and landmarks.

It also yielded World Heritage Gemstone No. 5 – Fragility of the Eternal (France), which depicted the pattern of the Notre-Dame Cathedral’s stained glass in the faceting diagram. The Spodumene (kunzite) version is a 3,051-carat stone with 914 facets, making it the largest faceted Spodumene to date. The 424.19-carat cubic zirconia version has 860 facets, representing each of the cathedral’s 860 years.

Each World Heritage project gemstone comes in two versions: Natural and synthetic gemstones.

The natural gemstone reflects the interaction between the master cutter and nature, while the synthetic material enables the lapidarist to fully realise his concept.

For instance, the refractive index and dispersion of cubic zirconia allowed Tuzlukov to replicate the effect of light passing through the stained glass of the Notre Dame Cathedral.

Sculptural prowess

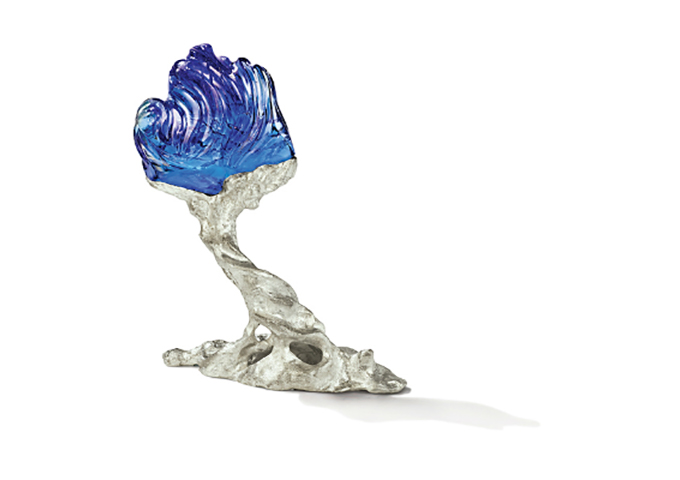

American artist, gem carver and sculptor Naomi Sarna is likewise committed to revealing fundamental truths through her exemplary pieces. Her work may be viewed at the Smithsonian’s Permanent Collection of American Gems.

Sarna’s masterpieces include the Stone of Heaven through exceptional carvings of jadeite and nephrite. She has won numerous awards for gem carving, including several for jadeite and nephrite carving at exhibitions in China. She is currently putting together the Jade Guild in the US.

Sarna was born within walking distance of some of the world’s greatest mineral mines in Butte, Montana. Minerals, gems and fossils were a part of her everyday life, and some of her early memories are of being in her grandfather’s store where miners came to shop and talk.

“Growing up, I had a sense of being able to do almost anything as long as I could do it with my hands,” she recalled.

As a classically trained sculptor, she had the opportunity to make magnificent, monumental pieces. At some point, she stopped making large pieces and shifted her focus to making precious art jewels.

“While Victor (Tuzlukov) and I approach our precious material in very different ways, we both appreciate that they come from the most ancient parts of the earth and we both see our work as a communication of spirit and emotion, as are all art forms,” said Sarna.

Personal touch

To find the best material for her craft, Sarna has travelled from Tanzania and Madagascar to Arkansas, visiting mines and hand-picking the rough gemstones that she turns into treasured objects.

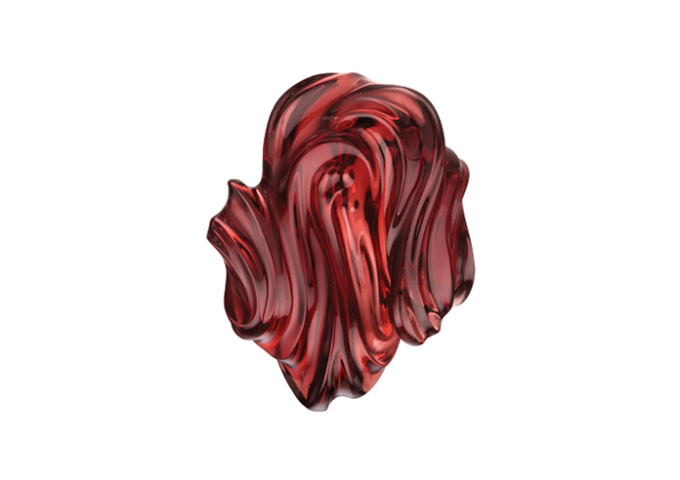

A female gem carver of the highest caliber is quite rare. Nothing has held back her creativity or drive. When Sarna looks at a rough gemstone, she knows within minutes what she will carve – the stone dictates the design. And while most carvers seek clean material, she prefers stones that have inclusions. These serve as the roadmap that guides her as she carves the stone.

Central to her work is the play of light and shadow, movement, texture and the use of bold colour combinations. Sarna feels an intimate connection to the gemstone she is carving – the design and outcome are constantly on her mind. It typically takes her 50 hours to carve a large gemstone but sometimes up to 500 hours to polish.

“It takes a certain state of mind to spend 500 hours polishing a piece. I prepare as if it were a spiritual ritual, from which I emerge stronger. I have walked on hot coals and I would rather walk 50 feet on hot coals than contemplate 500 hours of polishing. I just want to be with the piece and be one with it; it calls me. Carving a stone is a very intimate relationship. I imbue my spirit into a piece and the spirit flows back into me,” said Sarna.

While the gem artist admires the work of minimalist and abstract painters and sculptors, her style leans towards the sensuous curves and flowing curls of the Pre-Raphaelite and Art Nouveau periods.

“I’m always observing and seeking the beautiful line,” she revealed.

Indeed, Sarna’s works feature curves that are intertwined and sensuous. Collectors want to hold her pieces in their hands, feel their weight and see their beauty. Her works are made by hand and meant to be held by hand.

“My larger, stand-alone carvings are on bases, and can be removed and held as a focal point for a meditation. You want to hold them close, not have them at a distance from you. Wearing my art jewels with carved gems feel like they are a part of you,” she explained.